Yes, this Blog post does have OProfile examples and tips, but first my obligatory rant…

When it comes to Oracle on clustered Linux, FUD abounds. My favorite FUD is concerning where kernel mode processor cycles are being spent. The reason it is my favorite is because there is no shortage of people that likely couldn’t distinguish between a kernel mode cycle and a kernel of corn hyping the supposed cost of running Oracle on filesystem files—especially cluster filesystems. Enter OProfile.

OProfile Monitoring of Oracle Workloads

When Oracle is executing, the majority of processor cycles are spent in user mode. If, for instance, the processor split is 75/25 (user/kernel), OProfile can help you identify how the 25% is being spent. For instance, what percentage is spent in process scheduling, kernel memory management, device driver routines and I/O code paths.

System Support

The OProfile website says:

OProfile works across a range of CPUs, include the Intel range, AMD’s Athlon and AMD64 processors range, the Alpha, ARM, and more. OProfile will work against almost any 2.2, 2.4 and 2.6 kernels, and works on both UP and SMP systems from desktops to the scariest NUMAQ boxes.

Now, anyone that knows me or has read my blog intro knows that NUMA-Q meant a lot to me—and yes, my Oak Table Network buddies routinely remind me that I still haven’t started attending those NUMA 12-step programs out there. But I digress.

Setting Up OProfile—A Tip

Honestly, you’ll find that setting up OProfile is about as straight forward as explained in the OProfile documentation. I am doing my current testing on Red Hat RHEL 4 x86_64 with the 2.6.9-34 kernel. Here is a little tip: one of the more difficult steps to getting OProfile going is finding the right kernel-debug RPM. It is not on standard distribution medium and hard to find—thus the URL I’ve provided. I should think that most people are using RHEL 4 for Oracle anyway.

OProfile Examples

Perhaps the best way to help get you interested in OProfile is to show some examples. As I said above, a very important bit of information OProfile can give you is what not to worry about when analyzing kernel mode cycles associated with an Oracle workload. To that end, I’ll provide an example I took from one of my HP Proliant DL-585’s with 4 sockets/8 cores attached to a SAN array with 65 disk drives. I’m using an OLTP workload with Oracle10gR2 and the tablespaces are in datafiles stored in the PolyServe Database Utility for Oracle; which is a clustered-Linux server consolidation platform. One of the components of the Utility is the fully symmetric cluster filesystem and that is where the datafiles are stored for this OProfile example. The following shows a portion of a statpack collected from the system while OProfile analysis was conducted.

NOTE: Some browsers require you to right click->view to see reasonable resolution of these screen shots

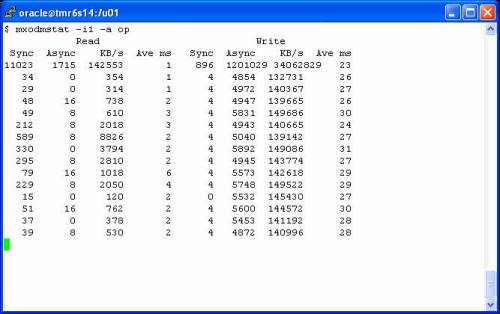

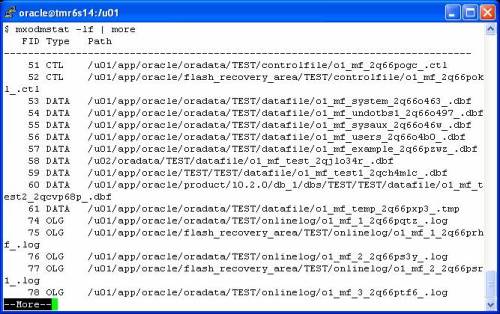

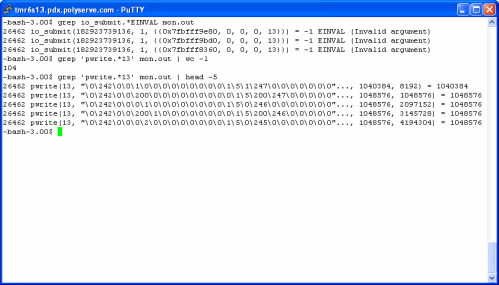

As the statspack shows, there were nearly 62,000 logical I/Os per second—this was a very busy system. In fact, the processors were saturated which is the level of utilization most interesting when performing OProfile. The following screen shot shows the set of OProfile commands used to begin a sample. I force a clean collection by executing the oprofile command with the –deinit option. That may be overkill, but I don’t like dirty data. Once the collection has started I run vmstat(8) to monitor processor utilization. The screen shot shows that the test system was not only 100% CPU bound, but there were over 50,000 context switches per second. This, of course, is attributed to a combination of factors—most notably the synchronous nature of Oracle OLTP reads and the expected amount of process sleep/wake overhead associated with DML locks, background posting and so on. There is a clue in that bit of information—the scheduler must be executing 50,000+ times per second. I wonder how expensive that is? We’ll see soon, but first the screen shot showing the preparatory commands:

So the next question to ask is how long of a sample to collect. Well, if the workload has a “steady state” to achieve, it is generally sufficient to let it get to that state and monitor about 5 or 10 minutes. It does depend on the ebb and flow of the workload. You don’t really have to invoke OProfile before the workload commences. If you know your workload well enough, watch for the peak and invoke OProfile right before it gets there.

The following screen shot shows the oprofile command used to dump data collected during the sample followed by a simple execution of the opreport command.

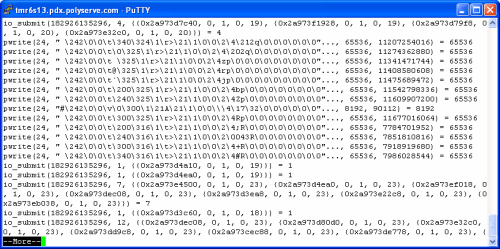

OK, here is where it gets good. In the vmstat(8) output above we see that system mode cycles were about 20% of the total. This simple report shows us a quick sanity check. The aggregate of the core kernel routines (vmlinux) account for 65% of that 20%–13% of all processor cycles. Jumping over the cost of running OProfile (23%) to the Qlogics Host Bus Adaptor driver we see that even though there are 13,142 IOPS, the device driver is handling that with only about 6% of system mode cycles—about 1.2% of all processor cycles.

The Dire Cost of Deploying Oracle on Cluster Filesystems

It is true that Cluster Filesystems inject code in the I/O code path. To listen to the FUD-patrol, you’d envision a significant processor overhead. I would if I heard the FUD and wasn’t actually measuring anything. As an example, the previous screen shot shows that by adding the PolyServe device driver and PolyServe Cluster Filesystem modules (psd, psfs) together there is 3.1% of all kernel mode cycles (.6% of all cycles) expended in PolyServe code—even at 13,142 physical disk transfers per second. Someone please remind me the importance of using raw disk again? I’ve been doing performance work on direct I/O filesystems that support asynchronous I/O since 6.0.27 and I still don’t get it. Anyway, there is more that OProfile can do.

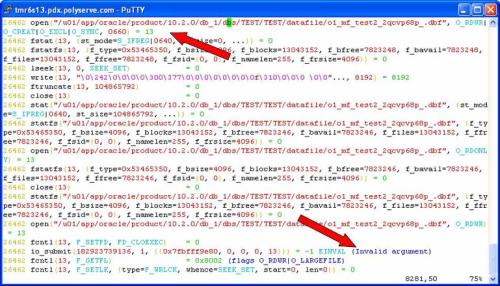

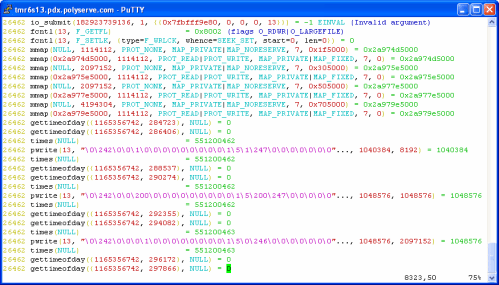

The following screen shot shows an example of getting symbol-level costing. Note, I purposefully omitted the symbol information for the Qlogic HBA driver and OProfile itself to cut down on noise. So, here is a trivial pursuit question: what percentage of all processor cycles does RHEL 4 on a DL-585 expend in processor scheduling code when the system is sustaining some 50,000 context switches per second? The routine to look for is schedule() and the following example of OProfile shows the answer to the trivial pursuit question is 8.7% of all kernel mode cycles (1.7% of all cycles).

The following example shows me where PolyServe modules rank in the hierarchy of non-core kernel (vmlinux) modules. Looks like only about 1/3rd the cost of the HBA driver and SCSI support module combined.

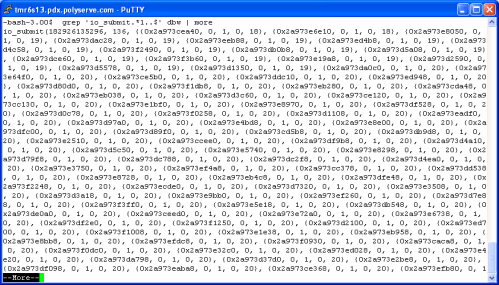

If I was concerned about the cost of PolyServe in the stack, I would use the information in the following screen shot to help determine what the problem is. This is an example of per-symbol accounting. To focus on the PolyServe Cluster Filesystem, I grep the module name which is psfs. I see that the component routines of the filesystem such as the lock caching layer (lcl), cluster wide inode locking (cwil) and journalling are evenly distributed in weight—no “sore thumbs” sticking up as they say. Finally, I do the same analysis for our driver, PSD, and there too see no routine accounting for any majority of the total.

Summary

There are a couple of messages in this blog post. First, since tools such as OProfile exist, there is no reason not to actually measure where the kernel mode cycles go. Moreover, this sort of analysis can help professionals avoid chasing red herrings such as the fairy tales of measurable performance impact when using Oracle on quality direct I/O cluster filesystems. As I like to say, “Measure before you mangle.” To that end, if you do find yourself in a situation where you are losing a significant amount of your processor cycles in kernel mode, OProfile is the tool for you.

Recent Comments