Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine – An Introduction

On October 1, 2012 Oracle issued a press release announcing the Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine. Well-chosen words, Oracle marketing, surgical indeed.

Words matter.

Games Are Games–Including Word Games

Oracle didn’t issue a press release about Exadata “In-Memory Database.” No, not “In-Memory Database” but “Database In-Memory” and the distinction is quite important. I gave some thought to that press release and then searched Google for what is known about Oracle and “in-memory” database technology. Here is what Google offered me:

Note: a right-click on the following photos will enlarge them.

With the exception of the paid search result about voltdb, all of the links Google offered takes one to information about Oracle’s Times Ten In-Memory Database which is a true “in-memory” database. But this isn’t a blog post about semantics. No, not at all. Please read on.

Seemingly Silly Swashbuckling Centered on Semantics?

Since words matter I decided to change the search term to “database in-memory” and was offered the following:

So, yes, a little way down the page I see a link to webpage about Oracle’s freshly-minted term: “Database In-Memory”.

I’ve read several articles covering the X3 hardware refresh of Oracle Exadata Database Machine and each has argued that Oracle Real Application Clusters (RAC), on a large-ish capacity server, does not qualify as “in-memory database.” I honestly don’t see the point in that argument. Oracle is keenly aware that the software that executes on Exadata is not “in-memory database” technology. That’s why they wordsmith the nickname of the product as they do. But that doesn’t mean I accept the marketing insinuation nor the hype. Indeed, I shouldn’t accept the marketing message–and neither should you–because having the sacred words “in-memory” in the nickname of this Exadata product update is ridiculous.

I suspect, however, most folks have no idea just how ridiculous. I aim to change that with this post.

Pictures Save A Thousand Words

I’m horrible at drawing, but I need to help readers visualize Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine at a component level. But first, a few words about how silly it is to confuse Exadata Smart Flash Cache with “memory” in the context of database technology.

But A Bunch Of PCI Flash Cards Qualify As Memory, Right?

…only out of necessity when playing word games. I surmise Oracle needed some words to help compete against HANA–so why not come up with a fallacious nickname to confuse the fact? Well, no matter how often a fallacy is repeated it remains a fallacy. But, I suppose I’m just being pedantic. I trust the rest of this article will convince readers otherwise.

If PCI Flash Is Memory Why Access It Like It’s a Disk?

…because the flash devices in Exadata Smart Flash Cache are, in fact, block devices. Allow me to explain.

The PCI flash cards in Exadata storage servers (aka cells) are presented as persistent Linux block devices to, and managed by, the user-mode Exadata Storage Server software (aka cellsrv).

In Exadata, both the spinning media and the PCI flash storage are presented by the Linux Kernel via the same SCSI block internals. Exadata Smart Flash Cache is just a collection of SCSI block devices accessed as SCSI block devices–albeit with lower latency than spinning media. How much lower latency? About 25-fold faster than a high-performance spinning disk (~6ms vs ~250us). Oh, but wait, this is a blog post about “Database In-Memory” so how does an 8KB read access from Exadata Smart Flash Cache compare to real memory (DRAM)? To answer that question one must think in terms relevant to CPU technology.

In CPU terms, “reading” an 8KB block of data from DRAM consists of loading 128 cachelines into processor cache. Now, if a compiler were to serialize the load instructions it would take about 6 microseconds (on a modern CPU) to load 8KB into processor cache–about 1/40th the published (datasheet) access times for an Exadata Smart Flash Cache physical read (of 8KB). But, serializing the memory load operations would be absurd because modern processors support numerous concurrent load/store operations and the compilers are optimized for this fact. So, no, not 6us–but splitting hairs when dissecting an absurdity is overkill. Note: the Sun F40 datasheet does not specify how the published 251us 8KB read service time is measured (e.g., end-to-end SCSI block read by the application or other lower-level measurement) but that matters little. In short, Oracle’s “Database In-Memory” data accesses are well beyond 40-fold slower than DRAM. But it’s not so much about device service times. It’s about overhead. Please read on…

High Level Component Diagram

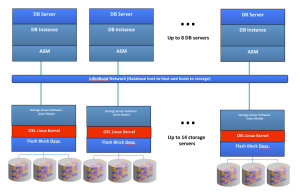

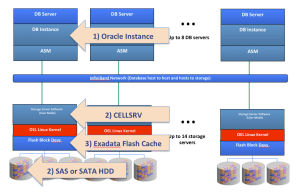

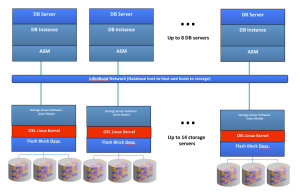

The following drawing shows a high-level component breakout of Exadata X3-2. There are two “grids” of servers each having DRAM and Infiniband network connectivity for communications between database hosts and to/from the “storage grid.” Each storage server (cell) in the storage grid has spinning media and (4 each) PCI flash cards. The cells run Oracle Linux.

Exactly When Did Oracle Get So Confused Over The Difference Between PCI Flash Block Devices And DRAM?

In late 2009 Oracle added F20 PCI flash cards as a read-only cache to the second generation Exadata known as V2–or perhaps more widely known as The First Database Machine for OLTP[sic]. Fast forward to the present.

Oracle has upgraded the PCI flash to 400GB capacity with the F40 flash card. Thus, with the X3 model there is 22.4TB of aggregate PCI flash block device capacity in a full-rack. How does that compare to the amount of real memory (DRAM) in a full-rack? The amount of real memory matters because this is a post about “Database In-Memory.”

The X3-2 model tops out at 2TB of aggregate DRAM (8 hosts each with 256GB) that can be used (minus overhead) for database caching (up from 1152 GB in the X2 generation). The X3-8, on the other hand, offers an aggregate of 4TB DRAM for database caching (up from the X2 limit of 2TB). To that end the ratio of flash block device capacity to host DRAM is 11:1 (X3-2) or 5.5:1 (X3-8).

This ratio matters because host DRAM is where database processing occurs. More on that later.

Tout “In-Memory” But Offer Worst-of-Breed DRAM Capacity

Long before Oracle became confused over the difference between PCI flash block devices and DRAM, there was Oracle’s first Database In-Memory Machine. Allow me to explain.

In the summer of 2009, Oracle built a 64-node cluster of HP blades with 512 Harpertown Xeons cores and paired it to 2TB of DRAM (aggregate). Yes, over three years before Oracle announced the “Database In-Memory Machine” the technology existed and delivered world-record TPC-H query performance results–because that particular 1TB scale benchmark was executed entirely in DRAM! And whether “database in-memory” or “in-memory database”, DRAM capacity matters. After all, if your “Database In-Memory” doesn’t actually fit in memory it’s not quite “database in-memory” technology.

Oracle Database has offered the In-Memory Parallel Query feature since the release of Oracle Database 11g R2.

So if Database In-Memory technology was already proven (over 3 years ago) why not build really large memory configurations and have a true “Database In-Memory? Well, you can’t with Exadata because it is DRAM-limited–most particularly the X3-2 model which is limited to 256GB per host. On the contrary, every tier-one x64 vendor I have investigated (IBM,HP,Dell,Cisco,Fujitsu) offers 768GB 2-socket E5-2600 based servers. Indeed, even Oracle’s own Sun Server X3-2 supports up to 512GB RAM–but only, of course, when deployed independently of Exadata. Note: this contrast in maximum supported memory spans 1U and 2U servers.

So what’s the point in bringing up tier 1 vendors? Well, Oracle is making an “in-memory” product that doesn’t ship with the maximum memory available for the components used to build the solution. Moreover, the Database In-Memory technology Oracle speaks of is generic database technology as proven by Oracle’s only benchmark result using the technology (i.e., that 1TB scale 512-core TPC-H).

OK, OK, It’s Obviously Not The “Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-DRAM Machine” So What Is It?

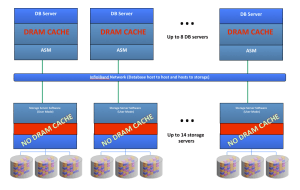

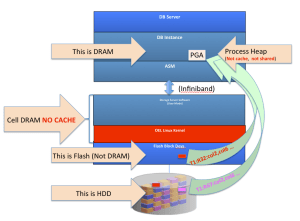

So if not DRAM, then what is the “memory” being referred to in Exadata X3 In-Memory Database Machine? I’ll answer that question with the following drawing and if it doesn’t satisfy your quest for knowledge on this matter please read what follows:

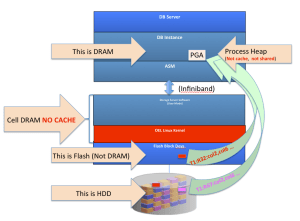

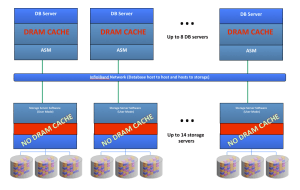

Presto-magic just isn’t going to suffice. The following drawing clearly points out where Exadata DRAM cache exists:

That’s right. There has never been DRAM cache in the storage grid of Exadata Database Machine.

The storage grid servers’ (cells) DRAM is used for purposes of buffering and the metadata managing such things as Storage Index and mapping what HDD disk blocks are present (copies of HDD blocks) in the PCI flash (Exadata Smart Flash Cache).

Since the solution is not “Database In-Memory” the way reasonable technologists would naturally expect–DRAM–then where is the “memory?” Simple, see the next drawing:

Yes, the aggregate (22TB) Exadata Smart Flash Cache is now known as “Database In-Memory” technology. Please don’t be confused. That’s not PCI flash accessed with memory semantics. No, that’s PCI flash accessed as a SCSI device. There’s more to say on the matter.

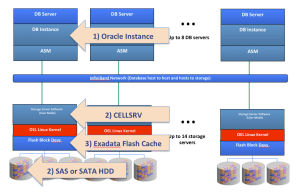

Please examine the following drawing. Label #1 shows where Oracle Database data manipulation occurs. Sure, Exadata does filter data in storage when tables and indexes are being accessed with full scans in the direct path, but cells do not return a result set to a SQL cursor nor do cells modify rows in Oracle database blocks. All such computation can only occur where label #1 is pointing–the Oracle Instance.

The Oracle Instance is a collection of processes and the DRAM they use (some DRAM for shared cache e.g., SGA and some private e.g., PGA).

No SQL DML statement execution can complete without data flowing from storage into the Oracle Instance. That “data flow” can either be a) a complete Oracle database disk blocks (into the SGA) or b) filtered data (into the PGA). Please note, I’m quite aware Exadata Smart Scan can rummage through vast amounts of data only to discover there are no rows matching the SQL selection criteria (predicates). I’m also aware of how Storage Indexes behave. However, this is a post about “Database In-Memory” and Smart Scan searching for non-existent needles in mountainous haystacks via physical I/O from PCI block devices and spinning rust (HDD) is not going to make it into the conversation. Put quite succinctly, only the Oracle Database instance can return a result set to a SQL cursor–storage cells merely hasten the flow of tuples (Smart Scan is essentially a row source) into the Oracle Instance–but not to be cached/shared because Smart Scan data flows through the process private heap (PGA).

Exadata X3: Mass Memory Hierarchy With Automatic What? Sounds Like Tiering.

I’m a fan of auto-tiering storage (e.g., EMC FAST). From Oracle’s marketing of the “Database In-Memory Machine” one might think there is some sort of elegance in the solution along those lines. Don’t be fooled. I’ll quote Oracle’s press release :

the Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine implements a mass memory hierarchy that automatically moves all active data into Flash and RAM memory, while keeping less active data on low-cost disks.

Sigh. Words Matter! Oracle Database does not draw disk blocks into DRAM (the SGA or PGA) unless the data is requested by SQL statement processing. The words that matter in that quote are: 1) “automatically moves” and 2) “keeping.” Folks, please consider the truth on this matter. Oracle doesn’t “move” or “keep.” It copies. The following are the facts:

- All Oracle Database blocks are stored persistently on hard disk (spinning) drives. “Active data” is not re-homed onto flash as Oracle press release insinuates. The word “move” is utterly misleading in that context. The accurate word would be “copy.”

- A block of data read from disk can be automatically copied into flash when read for the first time.

- If a block of data is not being accessed by an Exadata Smart Scan the entire block is cached in the host DRAM (SGA). Remember the ratios I cited above. It’s a needles-eye situation.

- If a block of data is being accessed by an Exadata Smart Scan only the relevant data flows through host DRAM (PGA) but is not cached.

In other words, “Copies” != “moves” and “keeping” insinuates tiering. Exadata does neither, it copies. Copies, copies, copies and only sometimes caches in DRAM (SGA). Remember the ratios I cited above.

Where Oh Where Have All My Copies Of Disk Blocks Gone?

The following drawing is a block diagram that depicts the three different memory/storage device hierarchies that hold a copy of a block (colored red in the drawing) that has flowed from disk into the Oracle Instance. The block is also copied into PCI flash (down in the storage grid) for future accelerated access.

Upon first access to this block of data there are 3 identical copies of the data. Notice how there is no cached copy of this block in the storage grid DRAM. As I already mentioned, there is no DRAM block cache in storage.

If, for example, the entirety of this database happened to fit into this one red color-coded block, the drawing would indeed represent a “Database In-Memory.” For Exadata X3 deployments serving OLTP/ERP use cases, this drawing accurately depicts what Oracle means when they say “Database In-Memory.” That is, if it happens to fit in the aggregate Oracle Instance DRAM (the SGA) then you have a “Database In-Memory” solution. But, what if the database either a) doesn’t fit entirely into host DRAM cache and/or b) the OLTP/ERP workload occasionally triggers an Exadata Smart Scan (Exadata offload processing)? The answer to “a” is simple: LRU. The answer to “b” deserves another drawing. I’ll get to that, but first consider the drawing depicting Oracle’s implied “automatic” “tiering”:

I’ve Heard Smart Scan Complements “Database In-Memory”

Yeah, I’ve heard that one too.

The following drawing shows the flow of data from a Smart Scan. The blocks are being scanned from both HDD and flash block devices (a.k.a Smart Flash Cache) because Exadata scans Flash and HDD concurrently as long as there are relevant copies of blocks in flash. Important to note, however, is that the data flowing from this operation funnels through the non-shared Oracle memory known as PGA on the database host . The PGA is not shared. The PGA is not a cache. The effort expended by the “Database In-Memory Machine” in this example churns through copies of disk blocks present in flash block devices and HDD to produce a stream of data that is, essentially, “chewed and spat out” by the Oracle Instance process on the host. That is, the filtered data is temporal and session-specific and does not benefit another session’s query. To be fair, however, at least the blocks copied from HDD into flash will stand the chance of benefiting the physical disk access time of a future query.

The fundamental attributes of what the industry knows as “in-memory” technology is to have the data in a re-usable form in the fastest storage medium possible (DRAM).

We see neither of these attributes with Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine:

It Takes a Synopsis To Visualize The New “In-Memory” World Order

I’m not nit-picking the semantic differences between “in-memory database” and “database in-memory” because as I pointed out already Oracle has been doing “Database In-Memory” for years. I am, however, going to offer a synopsis of what is involved when Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine processes a block in an OLTP/ERP-style transaction. After all, Exadata is the World’s First Database Machine for OLTP and now that it is also Database In-Memory technology it might interest you to see how that all works out.

Consider the following SQL DML statement:

UPDATE CN_COMMISSION_HEADERS_ALL set DISCOUNT_PERCENTAGE = 99 WHERE TRX_BATCH_ID = 42;

This SQL is a typical OLTP/ERP rowid-based operation. In the following synopsis you’ll notice how an Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine transaction requires a wee-bit more than a memory access. Nah, I’ll put the sarcasm aside. This operations involves an utterly mind-boggling amount of overhead when viewed from the rosy lenses of “in-memory” technology. The overhead includes such ilk as cross-server IPC, wire time, SCSI block I/O, OS scheduling time, CPU-intensive mutex code and so forth. And, remember, this is a schematic of accessing a single block of data in the Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine:

- On the Host

- Oracle foreground process (session) suffers SGA cache lookup/miss

- <spinlocks, SGA metadata block lookup (cache buffers chains, etc)>

- Oracle foreground LRUs a SGA buffer

- <spinlocks cache buffers LRU, etc>

- Oracle foreground performs an Exadata cell single block read

- Oracle foreground messages across iDB (Infiniband) with request for block

- <reliable datagram sockets IPC>

- Oracle foreground process goes to sleep on a single block read wait event

- <interrupt>

- <request message DMA to Infiniband HCA “onto the wire”>

- <wire time>

- On Storage Server

- <interrupt>

- <request message DMA from Infiniband HCA into Cellsrv>

- <Cellsrv thread scheduling delay>

- Cellsrv gets request and evaluates e.g., specific block to read, IORM metadata, etc

- Cellsrv allocates a buffer (to read the block into, also serves as send buffer)

- Cellsrv block lookup in directory (to see if it is in Flash Cache, for this example the block is in the Flash Cache)

- Cellsrv reads the block from flash Linux block device(Exadata Smart Flash Cache devices are accessed with the same library API calls as spinning disk.)

- Libaio or LibC read (non-blocking either way since Cellsrv is threaded)

- <kernel mode>

- <block layer code>

- <driver code>

- <interrupt>

- < DMA block from PCI Flash block device into send buffer/read buffer> THIS STEP ALONE IS 251us AS PER ORACLE DATASHEET

- <interrupt>

- <kernel mode>

- I/O marked complete

- <Delay until Cellrv “reaps” I/O completion >

- Cellsrv processes I/O completion (library code)

- Cellsrv validates buffer contents (DRAM access)

- Cellsrv sends block (send buffer) via iDB (Infiniband)

- <interrupt>

- <IB HCA DMA buffer onto the wire>

- <wire time>

- Back on Host

- <interrupt>

- <IB HCA DMA block from wire into SGA buffer)

- Oracle foreground process marked in runnable state by Kernel

- <process scheduling time>

- Oracle foreground process back on CPU

- Oracle foreground validates SGA buffer

- Oracle foreground chains the buffer in (for others to share)

- <spinlocks, cache buffers chains, etc>

- Oracle foreground locates data in the buffer (a.k.a “row walk”)

Wow, that’s a relief! We can now properly visualize what Oracle means when they speak of how “Database In-Memory Machine” technology is able to better the “World’s First Database Machine for OLTP.”

Summary

We are not confused over the difference between “database in-memory” and “in-memory database.”

Oracle have given yet another nickname to the Exadata Database Machine. The nickname represents technology that has been proven outside the scope of Exadata even 3 years ago. Oracle’s In-Memory Parallel Query feature is not Exadata-specific and that is a good thing. After all, if you want to deploy a legitimate Oracle database with the “database in-memory” approach you are going to need products from the best-of-breed server vendors since they’ve all stepped up to produce large-memory servers based on the hottest, current Intel technology–Sandy Bridge.

This is a lengthy blog entry and Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine is still just a nickname. You can license Oracle database and do a lot better. You just have know the difference between DRAM and SCSI block devices and choose best of breed platform partners. After all those of us who are involved with bringing best of breed technology to market are not confused at all by nicknames.

Sources:

- 25 years of Oracle and platforms experience. I didn’t just fall off the turnip truck.

- Exadata uses RDS (Reliable Datagram Sockets) with is OFED Open Source. The Synopsis of an Oracle-flavored “In-Memory” operation is centered on my understanding of RDS. You too can be an expert at RDS because it is Open source.

- docs.oracle.com

- Exadata data sheets (oracle.com)

- Google

- Expert Oracle Exadata – Apress

- http://www.oracle.com/technetwork/database/exadata-smart-flash-cache-twp-v5-1-128560.pdf

- http://www.oracle.com/technetwork/server-storage/engineered-systems/exadata/exadata-smart-flash-cache-366203.pdf

- http://www.aioug.org/sangam12/Presentations/20205.pdf

In other words, this is all public domain knowledge assembled for your convenience.

Recent Comments